Summary

- “Doing multiple things” is a foundational ability for any intelligent agent

- It’s also a persistent bugbear for RL agents, which typically comes at a cost

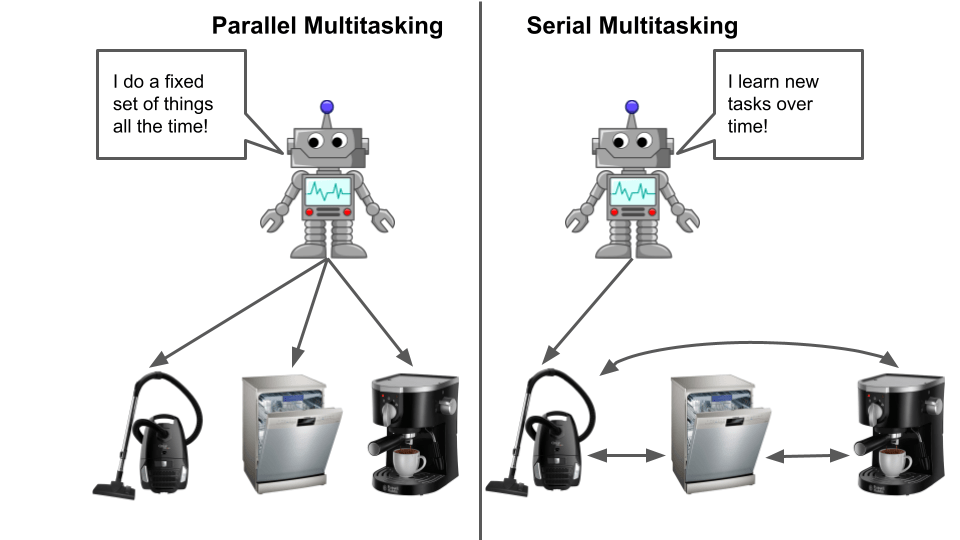

- There’s two versions of the multitask problem to consider:

- Parallel multitask, where tasks are simultaneous

- Sequential multitask, where tasks change between trials and may or may not repeat

- Of these, sequential multitasking is trivial for humans and animals and difficult for RL agents.

- How can we bridge that gap? Modularity may be key.

What does it mean to “Multitask?”

While a great deal of focus in modern machine learning is on improving performance on well-defined single tasks such as Imagenet classification, even the simplest animal must learn to perform multiple “tasks.” While some machine learning tasks can be learned and applied in isolation, most of the applications we imagine using reinforcement learning for (robotic manipulation, playing video games, conversing with humans, etc) inherently require some degree of multitasking. The fact that multitask RL is currently not very good is thus problematic.

As a human, when we think of multitasking we typically think of parallel multitasking, where we need to perform several tasks simultaneously (think texting while talking while walking). Ironically, this is relatively easy for an RL agent- it adds complexity to the action space and can increase overall difficulty, but isn’t fundamentally different from any other change to an MDP.

On the other hand, serial multitasking, in which an agent must learn and perform tasks which alternate periodically (think doing chores versus work), is trivial for humans but quite difficult for modern machine learning. As humans we usually don’t think of this as “multitasking” because it’s automatic- neurotypical humans don’t struggle to remember how to do multiple things in their daily lives, nor do they need to re-learn manipulation to interact with a new object. Despite (or perhaps because of) how easy these are for biological intelligence, they remain very difficult for AI. Solving this problem is a major challenge in modern reinforcement learning.

Approaches to Multitask RL

Let’s look in more detail at serial multitasking, and why it’s hard for RL algorithms.

In serial multitasking tasks, our RL agent needs to perform well on multiple (qualitatively different) tasks which are presented in alternating fashion. For humans “multitasking” usually implies that the tasks use the same regions of the brain*, but when using the term in an RL context we refer to something humans would consider to not be multitasking at all.

Serial multitasking is not about attention and context switching but about learning how to do multiple tasks at the same time. A human example of serial multitasking would be a chef preparing dishes as orders come in. Each dish takes a relatively short time to prepare (let’s say 15 minutes) and orders are sampled at random from a fixed menu, but the chef only prepares one dish at a time, giving it his full attention. The challenge for the chef is to know how to prepare every dish on the menu without forgetting how to prepare some of them, and to generalize technique used while making one dish to help with (or at least not hinder) learning to make new dishes.

If this sounds relatively straightforward, that’s because for humans it is. Humans (and most animals with brains) find learning and retaining multiple skills at the same time reflexive. Our skills can decay with lack of use, but we don’t forget skills (or perform worse at them) as a result of learning new ones*.

RL agents, like most deep neural network based machine learning algorithms, suffer from catastrophic forgetting– Learning to perform additional tasks will cause a neural network to forget other tasks. Further, sharing parameters between tasks may hinder performance compared to learning each task separately. For example, past work has found that naively training on many Atari games in parallel degrades performance, sometimes severely. While some methods can recover performance, in general training on multiple Atari games doesn’t improve overall performance, as most games seem to want distinct policies that don’t have much in common with other games.

Examples of successful multitask learning rely on careful curation of tasks such that they complement rather than conflict, effectively a form of curriculum shaping. To use our chef example, this would be like selecting a set of dishes that all contain similar ingredients prepared in similar fashion- if all the dishes contain grated carrot, it’s clear that there’s a technique (how to grate carrots) that will transfer between them, and our chef can more robustly learn to grate carrot in many contexts.

While humans can benefit from this sort of curriculum shaping*, we also don’t rely on it to learn multiple skills. Humans can segregate the neural circuits used for non-complementary tasks automatically, and seem to re-use shared subskills (more on this in the next section). This problem -figuring out what to share and what to keep separate- seems to be the key to successful multitask learning. A good solution will help with most of the issues encountered in multitask learning, and by extension generalization. I’ll refer to this issue as the sharing problem below.

Solving the Sharing Problem: Modularity

While at first blush a distinct problem from serial multitasking, modular RL is relevant as it offers a framework for solving the sharing problem, as well as the related problem of fast adaptation to new tasks.

The basic assumption of modular RL, also called Hierarchical RL*, is that any given task can be decomposed into some set of (discrete/non-overlapping) subtasks or subskills, which we are (for practical purposes) assuming to be shared between multiple tasks. To use the cooking example from earlier, each dish involves a series of steps to prepare (for example, finely chopping a vegetable) with most steps shared between multiple dishes. Those steps in turn may have additional substeps (such as placing the vegetable on a cutting board, picking up the knife, and the atomic action of cutting), descending to the level of motor control and moment-to-moment motion planning depending on how fine-grained we want to get.

Ok, this sounds reasonable on paper, but how do we know this sort of decomposition into modules will actually help multitask learning? We know this because it’s already been demonstrated, repeatedly, just not with a learned decomposition.

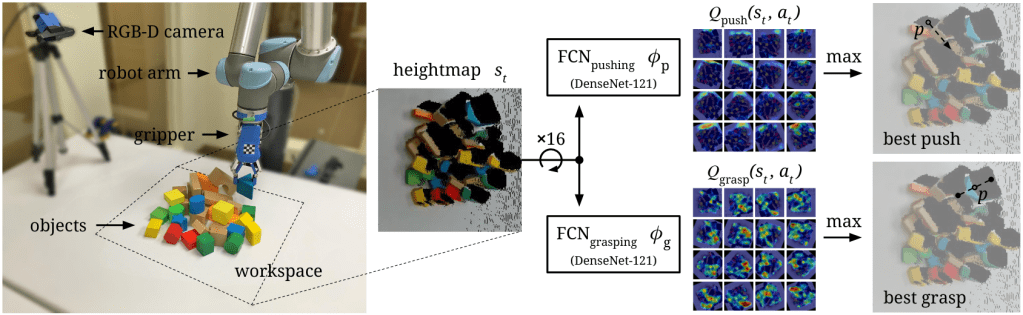

For example, there’s a body of work in robotics showing how RL can be combined with low-level motion primitives in a 2-level hierarchy (with one level being hardcoded), which learn much faster and generalize better than end-to-end RL methods trained on-robot. While not described as such, handcoded motion primitives are a form of (non-learned) modular subpolicy, meaning we can expect to see similar benefits if we can learn a good set of modules on some prior task before learning to pick up blocks.

The inverse (fixed high level, learned low level) has also been attempted. Research using a human-provided list of subtasks or a decomposed language prompt where learned modules are composed in a prescribed order reported large improvements in learning speed and generalization to new tasks compared to monolithic baselines.

In another domain, the recent NetHack Challenge led to the surprising result that symbolic agents (rules-based AI’s which decompose the game into known subtasks based on human-provided heuristics and search) are massively superior to RL agents on the text-based game NetHack, beating the best RL-using agent (a hybrid RL/symbolic method) by 300%.

If we stretch the definition of “AI” even further, we can even argue that humans create modular “agents” all the time. By breaking a complex problem into subproblems and developing techniques or machines that solve each of those individually (for example, modern electronics- we don’t need to redesign our microprocessors to write new software, usually), we are performing the same sort of decomposition we’d like our RL agents to be able to do automatically. While we humans usually decompose much harder problems than I’d expect RL agents to tackle in the near future, this is evidence that modularization is a good approach to understanding and interacting with the world in practice.

Now here’s the kicker: It’s clear that humans can write down effective decompositions for many tasks, but we don’t understand our own process well enough to automate it.

Assuming a modular structure exists in the tasks we are trying to solve*, the core challenge here is to automatically discover modules which when combined will solve our set of tasks.

How do we learn a decomposition?

tl;dr we have no idea

More eloquently, while we have a number of frameworks for how to represent modules, learning a good decomposition for (non-tabular) RL environments remains a largely unsolved problem.

At its heart, this is (probably) the result of two hard subproblems:

First, what exactly does a “module” represent? If we say “it’s a sub-policy solving some component of a higher-level task” (a reasonable enough definition IMO), should a module be a sequence of ~5 actions within a 1000-step task, or a sequence of ~500 actions? In a human context, does one module perform a tiny motor coordination step such as “close your fingers”, or a mid-level skill like “pick up your mug” or a higher-level objective like “make coffee” when the top-level policy (your conscious mind) is trying to get to work on time?

Second, assuming we have a timescale and semantic scope for our modules, which modules are useful to learn? If we only ever learn on a single task (for example, a robot picking up a cup on a table in exactly one configuration) we will struggle to learn modules that are useful for new tasks because the agent has no notion about what future tasks might look like or what skills they will require.

On the flip side, an agent that sees a broad and representative distribution of tasks at training time doesn’t need (explicit) modules- based on the current state of the art in RL it will probably generalize well to new in-distribution tasks (though acquiring and training on such a representative task set is a huge challenge in itself)

Success here will require some sort of structural prior about the relationships between previously-seen tasks and future unseen tasks.

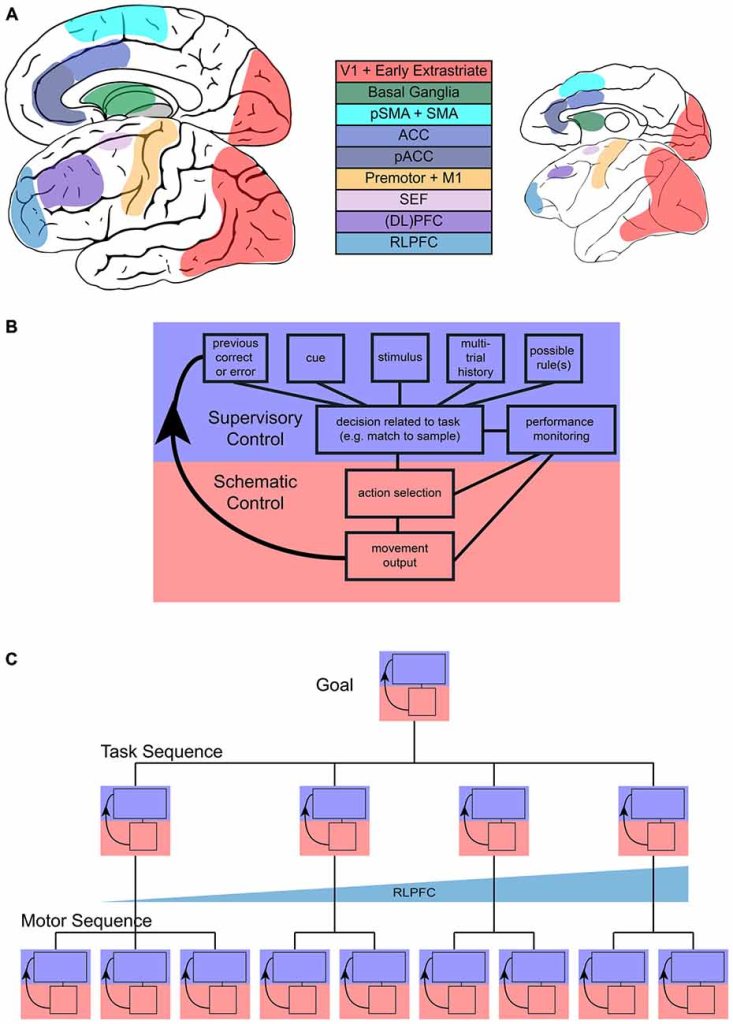

One possible prior comes to us from neuroscience: Experimental evidence suggests that the biological process of motor control involves multiple brain regions and does not draw a clear boundary between high-level and low-level actions. Rather, there’s evidence that low-level “schematic” policy modules imitate those behaviors of high-level “supervisory” policies which are frequently performed. Then, given a new task, the supervisory policies either select among existing low-level modules to execute or act directly in the primitive action space (potentially learning new schematic modules if this task reoccurs enough).

At a high level, this architecture assumes that action sequences/subtasks which are frequently encountered will continue to appear in future tasks. While there’s a lot that isn’t known about how this system learns*, the basic intuition (future tasks will be in whole or in part combinations of subtasks from previously seen tasks) checks out IMO.

Existing Modular RL Frameworks

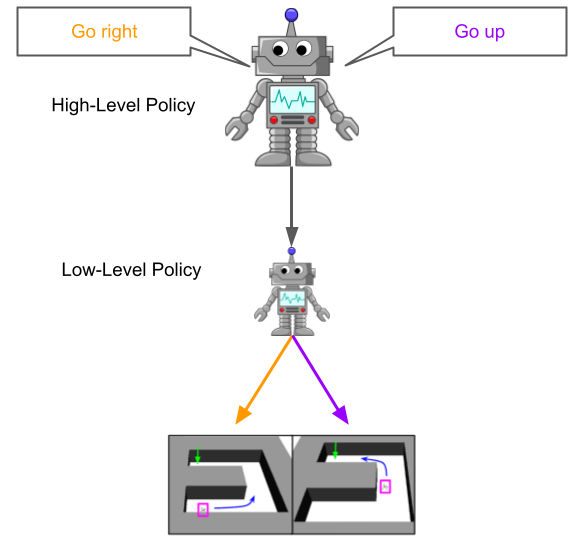

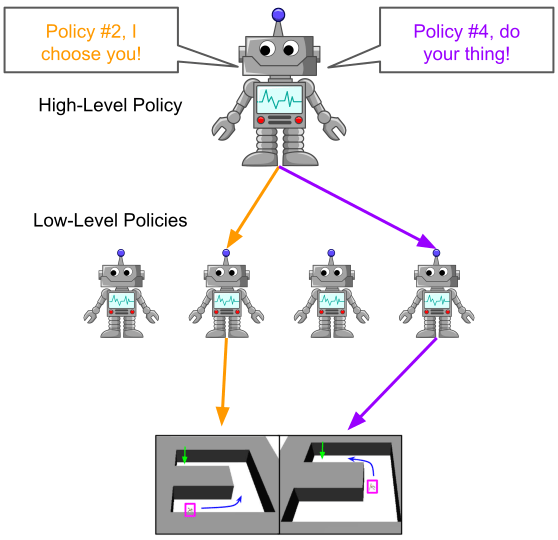

So what other approaches to modularity are out there? While a wide range of approaches with explicit hierarchical modules have been proposed, the two main ones that have found some success in the deep RL world recently are goal-conditioned hierarchy and options. In each case, the algorithm consists of a high-level policy which selects among possible high-level actions (usually less frequently than the base environment timestep), and a low-level policy conditioned on the high-level action which executes actions in the environment’s action space.

To describe them briefly, in goal-conditioned hierarchical RL, the high-level policy selects actions by specifying a goal (for example, move to some coordinates), which the low-level policy then tries to reach. In the options framework, the high-level policy’s actions select among a set of low-level policies, which once selected will execute whatever actions they have learned to perform.

Interestingly, both families of algorithms can easily reduce to traditional RL if poorly parametrized or in an environment that doesn’t benefit from modularity. In a goal-conditioned framework the first (and only) goal could simply be “the solution state,” while one option could represent “solve the task” with the other options being “immediately hand control back to the high-level policy.” This is nice for tasks with no useful modular structure, as these methods shouldn’t perform much worse than a standard RL method. However, it also means these methods must balance learning a modular solution to a task versus solving it directly without modularity (which might be faster to learn but less robust).

Another approach to modular learning that’s achieved recent popularity is unsupervised skill discovery, which is agnostic to explicitly modular frameworks like options but can be combined with them. Here, the objective is to learn skills/subtasks through exploration without external reward feedback, which will hopefully serve as useful priors once reward is introduced. While a number of methods (for example) have been proposed that can discover non-trivial skills in common benchmark domains like Mujoco tasks, The main limitation to this approach is that it is unsupervised (as per the name)- you can’t expect the discovered skills to be well-suited for specific future tasks, as they are completely task-agnostic. A recent paper explores this point theoretically and notes that while the skills discovered can be optimal with respect to regret against an adversarially chosen reward function, there’s no guarantee they will be optimal (or useful) for any reward function of human interest.

Open Questions

While hierarchical/modular RL and skill discovery are established research problems, the degree to which existing methods can solve the multitask sharing problem (especially for unseen future tasks) is unknown- most work on these methods has focused on single-task problems (more efficient learning for hierarchical RL, better initial policy for skill discovery), and their effects on multitasking/generalization are unknown.

The problem of discovering modular skills which are useful for tasks of human interest -including future tasks not seen in training- remains largely unexplored, as far as I’m aware. One aspect that has been looked at a little bit is whether representations learned through supervised learning contain compositional structure (implicit modularity in the trained network), such as this paper showing compositionality in RNN activations when trained on computational analogs to common neuroscience tasks. While this suggests modular behaviors might be discoverable through curriculum shaping, it’s not clear how common this phenomenon is or how far it could go.

It’s also worth considering the other side to this problem- how can we structure sets of tasks (or identify existing task sets) which have a shared modular structure? Some task sets will obviously share more structure than others, but what degrees and types of similarity allow for more or less sharing of learned modules? For example, Atari games have some commonalities- objects tend to move smoothly, bumping into them with your avatar tends to result in interaction (good or bad), and so on, but these are relatively low level and the actual policies for each game tend to be very different.

To conclude, there’s a lot we don’t know about modular RL methods and how they interact with multitask learning, partially due to how the field has segmented the space of RL research topics. Existing work on modular and hierarchical RL algorithms has mostly focused on single-task learning, while the multitask RL literature has focused on solving the sharing problem for monolithic architectures. Additionally, multitask RL has a split between methods which address multitasking during training (often called “multitask RL”) and those which improve performance on new tasks post-training (often called “meta-RL”), which might make it harder to discover holistic solutions that require and address both.

My hope is that the unifying view I’ve laid out here is useful in connecting these topics, which have been considered separate. Their intersection is an unexplored approach to the problem which has intuitive and biological grounding. If we can improve RL multitasking through modularity, our agents may yet be able to walk and chew bubble gum at the same time.

Footnotes

^ For example, most humans can talk while walking or driving without difficulty, but can’t write and speak at the same time, so “multitasking” means rapidly switching between tasks.

^ For example, if one takes classes in multivariable calculus and neural network machine learning at the same time or back to back the overlapping topics can improve understanding of both.

^ Hierarchical RL is the more common term, but personally I think it’s overly prescriptive and suggests a particular type of modularity (hierarchical modules), which isn’t the only possible architecture.

^ This is a fundamental assumption we are making here, which may or may not be true for a given MDP. Some standard benchmarks might not have meaningful modularity and thus not benefit from these methods. A recent paper addresses this topic in more theoretical detail and shows that you can even get major regret gains for a single MDP as long as modular structure exists.

^ Indeed, standard deep neural networks are modular by virtue of the independent neurons in each layer, and there’s evidence that a given input only activates a sparse set of neurons in converged networks, suggesting that learned modularity is common. We’re assuming here that there exists a smarter way to learn modularity than this, however.

^ There are some adversarial cases that break this, such as the “backwards bicycle.” In this case the two tasks (riding a normal bike and an inverse bike) are so similar it’s hard for a human to learn to do both at the same time unless they practice both styles.

^ For example, it’s still unclear what the scope of a schematic subpolicy should be, or how that scope might be determined during the learning process. It’s also unclear how exactly “frequently encountered subtasks” gets defined, or what constitutes one subtask- is it a specific sequence of motor activations that gets memorized, or is it adaptive? If it is adaptive, where do we draw the line between adapting an existing schematic module and simply using/learning a new one?