Summary

- Generalization is an intuitive concept that is stubbornly hard to quantify

- When people talk about “generalization” they mean one of several things:

- Invariance to inputs/observations/environment

- Invariance to changes in task/labels/reward function

- It would be useful to know how different two RL tasks are (and thus how hard generalization is) but this is intractable in general

- I discuss different approaches to generalization- zero-shot versus few-shot

- I conclude with some analysis of what makes this problem hard for RL agents compared to animals, and also some hot takes on what might help close the gap

Anyone who is passingly familiar with reinforcement learning knows that getting an RL agent to work for a task, whether a research benchmark or a real-world application, is difficult. Further, there’s no one reason for this, and the causes span both the practical and theoretical. In this post, I’m gonna go into detail on one such obstacle: generalization.

What is “Generalization?”

Generalization is a major bugbear in practical reinforcement learning (and all machine learning, to be fair). At a high level, generalization is simple- A learning agent trained on one set of experiences that can still perform it’s intended task given new experiences has generalized to the new data. Humans and animals do this all the time- when you want to pick up an unfamiliar object (say a miniature figurine from a board game you’ve never seen before) you don’t have to think about it or try multiple times (usually)- your prior experience picking up objects of all sorts means you generalize easily to new objects.

Animals can do this too- in a previous house of mine we had a mouse problem, and decided to use no-kill traps to deal with them. Whenever we caught a mouse I’d ride my bike out to a forested park a mile or two from the house (to ensure they can’t find their way back) and release them. I watched how the mice behaved in this situation: They were dropped into an unfamiliar forest they hadn’t seen before, and asked to quickly generalize to their surroundings in order to escape from the scary human lurking nearby.

In every case, the mice quickly (with less than a minute of observing their new environment) adapted their behavior, using bushes and leaves for cover and camouflaging themselves against tree trunks. While the environment was unfamiliar, there was functional similarity to other environments they’d seen (bushes, trees, fallen leaves, etc), so adaptation was fast.

Sad to say, even the best reinforcement learning agent today pales in comparison to that mouse. The idea of generalization in RL is intuitive and instinctual for humans, but we don’t really know how to get there yet.

Generalization in RL

So what does generalization look like in an RL context? Broadly put, it’s a matter of invariance to changes in the distribution of states/rewards. If the data our agent is trained on is sampled from a distribution that contains everything we expect it to ever see, (in theory) we don’t need to worry about generalization if we simply sample enough data*. In practice, this is intractable for most applications. Even for the mouse above, while it has surely seen trees, grass, and leaves before, there’s no way to densely sample the full distribution of foliage in a mouse’s lifespan*.

Given that our agent will eventually see things outside it’s data distribution, there’s two types of variation that we’d like RL agents to be robust to*:

- Variation in observation/state/transition function (new environment, same task)

- Variation in reward function (same environment, new task)

It should be obvious that these are intractable in general- if we change the environment so dramatically as to be unrecognizable, even a human will fail to generalize. Likewise, there are degrees of variation so small that generalization is trivial for even a naive agent. When we talk about generalization, it is important to reason about how different the training and evaluation distributions are.

Measuring generalization is hard in general

What makes this tricky is that “how different is MDP A from MDP B?” is a hard question to answer- we don’t have any good distance metrics, and it’s not clear how to begin to formulate them. Consider the Atari games Frostbite, Amidar, and MsPacMan:

It’s not obvious how to compare these MDPs, whether visually or functionally. Amidar and MsPacMan both have the agent moving through passageways, avoiding enemies and ultimately covering every passage in a level to clear it. As humans, we can qualitatively say these two environments are similar, but how can we represent that similarity quantitatively?

Even harder, Frostbite is also similar to the other two- it’s an Atari game (similar visuals and dynamics), has levels, involves control of a single agent in a 2D environment, and so on. How similar are Frostbite and Amidar compared to a game like Starcraft?

General Approaches to Generalization

Thus, a necessary precondition for any type of agent generalization is that we believe that the agent’s training domain is informative enough about the test domain to allow some degree of generalization. That said, in even the best case zero-shot transfer learning (generalizing an agent to a test domain without any further learning on that domain) will result in some degree of performance loss.

That said, what approaches can help improve generalization? Let’s go over a few:

Invariance to Observations

Improving how observations are represented is by far the best way to improve robustness to type 1 variation (different environment, same task). Consider for example the following robots, which are controlled by RL policies given images like the ones below:

These two robots do the same task- they pick miscellaneous small objects out of a bin. The environmental structure is the same (bins of similar dimensions, if not the exact same bins, as the two papers from from the same group), and the robots function very similarly.

However, when the authors tried to substitute one robot arm for the other (in the journal version of the earlier paper), they found that the RL policy they had learned on one did not generalize to the other. The reason? The observations were different- specifically, the robot arm in the picture was different. This RL agent is trained on hundreds of thousands of grasp attempts, and can generalize to new objects reliably, but can be foiled by simply painting the robot arm a different color.

This sort of behavior is common in RL- agents will behave badly when aspects of their environment are changed which did not vary during training, including trivial details that are irrelevant to the task at hand, such as the color of a robot arm.

The way to address this is to change how the environment is represented. For example, in the robotic task above we could replace RGB images with a non-image-based representation (such as predicted object positions from another neural network), meaning the two robot arms would appear the same to the agent, which would therefore generalize much better.

Input feature engineering is not always easy, however- it can be time consuming and difficult, or even impossible*. In such cases, there’s a few tricks we can use:

- We can change our neural network architecture to limit it’s ability to overfit.

- Bottlenecks (low dimensional internal network representations) are a common way to do this, in the hopes that if we limit the number of bits used to represent the input extraneous information will be ignored and only task-relevant information will be used for decision making.

- We can augment our inputs to add variation that isn’t naturally present in the training distribution.

- Domain Randomization is the most extreme form of this. Varying many aspects of a robotics simulation that don’t vary in the real world will make an agent trained only in simulation generalize better to the real world, as those aspects (such as lighting) are not perfectly simulated to begin with.

- We can (pre-) train a representation that maps functionally similar states to the same/similar representations.

- A recent example of this is the idea of bisimulation. Two states are considered bisimilar if they are functionally identical, but appear different. Some recent work has sought to learn representations that preserve bisimilarity and found this aids robustness to background details in image observations.

Limitations

Recent work on this topic has shown progress on robustness to distractors, such as different background details, image perturbations, and so on. One big question is how to handle perceptual analogies, where the presentation of task-relevant information changes partially. As a visual example, consider the case of stop signs:

If an agent has learned “stop signs are red octagons with ‘stop’ on them” it will react poorly to unusual stop signs that don’t follow that rule. In principle we can imagine augmenting our environment to include randomized stop signs, but repeating that process for every possible point of variation is very expensive in both human and compute time.

For each of the examples above, a human will (usually) recognize the intent behind the sign and react accordingly, even if (like me) you’ve only ever seen one design of stop sign when driving. The part that makes this hard for RL agents is there’s no single element that’s encodes “this is a stop sign” but rather a collection of elements that make a sign more or less “stop sign-y.” If we’re learning a representation for our agent that representation needs to encode each of the above similarly without seeing more than one stop sign design in advance.

This issue shows up in other domains of ML besides reinforcement learning, but one advantage RL might have in solving it is that observations are functionally grounded. That is, we don’t just want to recognize stop signs as arbitrary objects, our goal is to (for example) drive correctly, which includes (but isn’t limited to) recognizing and reacting to signage. When a human sees a stop sign it’s not as a single patch of pixels- there’s a context in which a knowledgeable driver expects the sign to be a stop sign versus some other type of sign, such as an intersection, which can help fill in some of the gaps. Consider the following example, where I blocked out the sign that was present:

Here, it’s easier to make a functional analogy (this seems like a spot where we should stop, given a 4-way intersection and a crosswalk) than to make a visual analogy (the sign is a gray square, it’s impossible to tell if it’s a stop sign or not). This functional grounding also shows up in the mouse example at the beginning: while this collection of groundcover looks very different from others the mouse has seen, it’s functionally very similar.

Invariance to Reward Functions

So observational invariance makes sense, but what about the case where two environments are not functionally identical?

Typically in this case we don’t expect a policy learned on task A to generalize seamlessly to a related but different task B. Solutions tend to fall into two categories:

- Few-shot learning: Given a pre-trained policy/model, adapt to a new task given relatively few interactions (or only offline data).

- Zero-shot learning: Rather than adapt the model in response to seeing a new task, “pre-adapt” the model using things like regularization or training curricula such that task B is “more similar” to tasks that the model has seen before than would naively be the case.

It’s worth noting the two approaches are not mutually exclusive- An RL agent could use an augmented training process to train on tasks that are “more similar” to expected test time tasks while also encouraging fast adaptation at test time using techniques like meta-learning. The main distinction (to my mind) is that the first focuses on how to improve learning on new tasks, while the second tries to learn a more general model on the original task(s).

This area is very active currently, with a number of major approaches proposed. A recent survey paper covers the literature quite well, but I’ll briefly note some major directions:

There’s a recent paper out of UC Berkeley which frames generalization as introducing a POMDP in what might otherwise be a fully-observed MDP due to the unobserved observation/reward function distributions, which is worth a read. Their framework also serves as a good motivation for few-shot methods, which can be thought of as analogous to information gathering in a conventional POMDP.

In the few-shot learning/active adaptation category, meta-learning is currently very popular, and has come to describe the few-shot problem at large. On the zero-shot side, offline RL has recently gotten a lot of attention, particularly for robotics. Other approaches of recent note include domain randomization, large offline RL datasets, adversarial environment design (and the broader category of curriculum learning), and unsupervised skill learning.

Limitations

The major limitations of current methods are mostly around generalization distance, as might be expected. Current approaches can often transfer well to new tasks that are similar to previously seen tasks, but remain brittle to types of variation not seen during training.

That test tasks which are very different from training tasks are harder is unsurprising, but the degree of difference that can be handled is quite limited in most cases. Further, it is hard to predict “how different” tasks can be without performance collapsing, or what types of variation will cause issues.

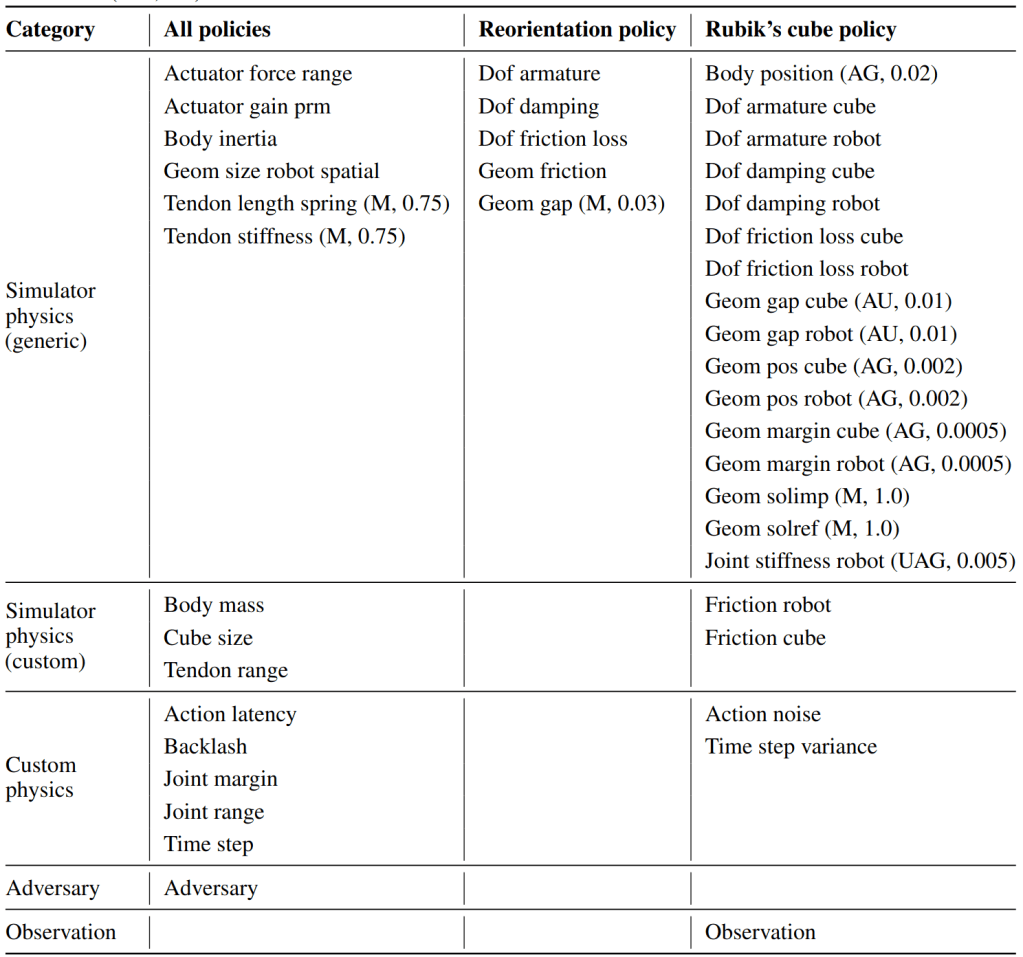

Let’s look at the example of domain randomization: Given sufficient effort and a lot of compute it’s possible to make an RL agent trained in simulation generalize to the real world, which is a non-trivial generalization gap. However, this relies on the manual process of identifying which simulator variables are different from the real world. Consider the table of variables from OpenAI’s Rubik’s cube solving robot paper:

Most of these variables are application-specific, and their importance must be discovered through trial and error (train in sim, run on the robot, see if it works). While the end result transfers impressively well to the real-world robot, there’s no general way to tell in advance what environment variables a policy will need to generalize across, so this reliance on manual discovery and designed curricula is likely hard to overcome in the 0-shot case.

As a practical note of hope, I suspect that there are common application domains where a semi-consistent set of variables are sufficient for task in that domain. For example, I could see a “common parameter set” for robotic manipulation tasks using a robot arm where individual researchers only need to reason about task-specific environment variables (for example, how to vary a rigid block versus a flexible cloth, while the robot’s variables are varied in the same way).

If out-of-the-box 0-shot generalization is so hard, how about few-shot? In principle the problem is simpler- rather than know what variables will change in advance we just need to be able to adjust to the novelty we do see quickly. In practice, however, the core issue is similar- deep neural networks have a tendency to overfit to unchanging elements of their input (including task-agnostic ones, as noted before), and thus fast adaptation is easiest when given a test task which varies in the same ways that training tasks do.

As a result, fast adaptations such as “run a different direction than previously seen” are achievable when trained to run in different directions, while “go the usual direction, but hop instead of run” is not.

Research Questions

So are we doomed to forever suffer on out-of-distribution tasks? Based on the example of human motor skill learning, hopefully not: A human can pick up many “out of distribution” motor skills with limited practice, though mastery can take years*. In addition, humans (usually) know how to learn new skills safely- regardless of the novelty of the skill we can estimate what states are dangerous and (mostly) avoid them. This suggests our world model and value estimation generalize well even when our motor control policies don’t- we know “what” we want to do in a novel task even if we don’t know “how” to do it.

How about the mouse from the beginning? We do see something similar to the out-of-distribution problem in that training mice to solve laboratory problems is a slow and fragile process full of careful curriculum shaping*, but recent work suggests this may be a result of the highly-constrained nature of these typical lab tasks, and that a free-roaming mouse will learn much faster. At the same time, mice can adapt to new environments quickly and robustly (though I’d guess that wild survival rates for mice dropped into a new biome as adults will be lower than for mice raised in that environment). It’s clear that mice have better prior ability to adapt to some new tasks than others, but their generalization within familiar task types is much broader than even the best RL agent’s today.

I suspect the crux of the issue lies here: How do we go from generalization determined by low-level visual and environmental features to generalization depending on high-level functional similarities*? Some of this can possibly be explained by the richness and diversity (or lack thereof) of the training environments used in RL versus mice in the real world, but the sheer breadth of variation a mouse can adapt to suggests there’s more to this question than just data.

Most likely there isn’t just “one weird trick to solve intelligence” either- a number of factors are clearly involved, from the sometimes-sensitivity of neural networks to variation in input values to how readily RL agents learn to rely on spurious correlations. Disentangling these factors is gonna be a slow process, but I think it’s probably the most important problem to solve in reinforcement learning today.

Footnotes

^ Let’s set aside the question of “how much data is enough?” for another day… 🙂

^ Evolutionary “pretraining” might help, but the distribution of trees is still broad, and the organism risks overfitting since evolution can’t adapt quickly to changes in distribution. This clearly happens in some cases (extinction due to environmental change), but mice are so adaptive to unforeseeable changes in environment (living inside human homes) that I have a hard time attributing all of their generalization to good evolutionary priors.

^ Note that we can have both of these at the same time, or only one. It’s also possible to have variance in the action space, but this is less common and requires learning new parameters or generalizing the action space such that the change is better expressed as a change of state space/transition matrix.

^ For example, comparing even well-behaved reward functions of 64×64 pixel natural images is impossible, because the set of natural images is much smaller than the set of all possible 64×64 images (most of them look like static), and that’s before getting to the “what subset of natural images will we ever see” question.

^ In the example solution from the previous paragraph I assumed we had access to another neural network that can “hide” the variation from the agent and learn invariance more easily, but sometimes this sort of pretrained network doesn’t exist, or comes with significant drawbacks.

^ For example, humans don’t have much intuition about how to ice skate without having done it before, but most humans can learn to ice skate relatively fast, and can move on the ice (mostly) without falling within an hour. However becoming an Olympic-level skater takes decades of constant practice totaling tens or hundreds of thousands of hours.

^ For example, I have a friend who once taught mice to track the number of markers on the left versus right side of a corridor as it ran through a maze. This process took months, involved a curriculum of multiple mazes, and pushed the limits of mouse cognitive ability- some candidate mice simply couldn’t do the more complex tasks even after many trials. Smarter animals like rats, cats, or apes (and of course humans) however can perform similar tasks with fewer trials and less curriculum shaping despite the task being “out of distribution” for them as well, which hints that smarter animals are also better general-purpose learners.

^ If we could stick an RL agent in a mouse body, our best RL agents would probably struggle to generalize to things like “the sky looks different today” or “this one rock got moved that I was relying on for navigation,” whereas mice can effortlessly handle such variations.